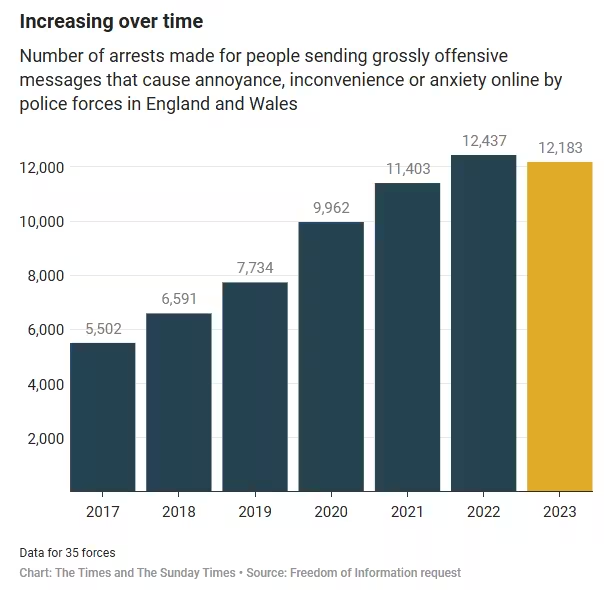

Thousands of people are being detained and questioned for sending messages that cause “annoyance”, “inconvenience” or “anxiety” to others via the internet, telephone or mail.

Custody data obtained by The Times shows that officers are making about 12,000 arrests a year under section 127 of the Communications Act 2003 and section 1 of the Malicious Communications Act 1988.

The acts make it illegal to cause distress by sending “grossly offensive” messages or sharing content of an “indecent, obscene or menacing character” on an electronic communications network.

The statistics have provoked criticism from civil liberties groups that the authorities are over-policing the internet and threatening free speech using “vague” communications laws.

As director of public prosecutions, Sir Keir Starmer issued Crown Prosecution Service guidance stating that offensive social media messages should only lead to prosecution in “extreme circumstances”.

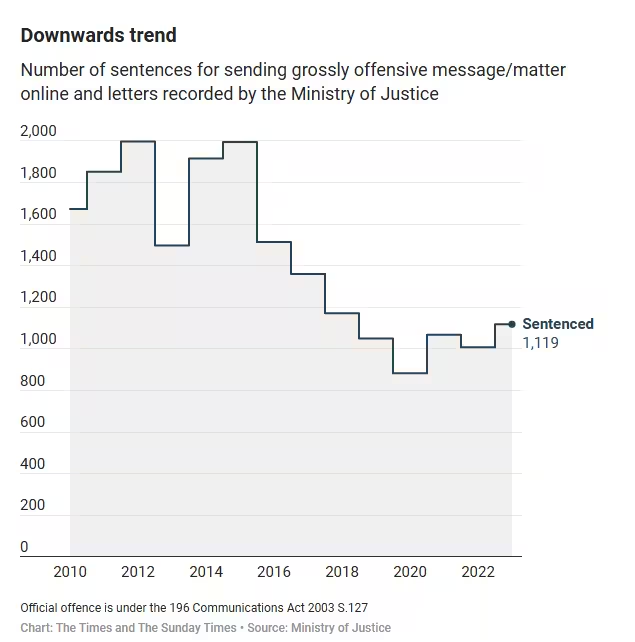

Analysis of government data shows that the number of convictions and sentencings for communications offences has dramatically decreased over the past decade.

There are several reasons for arrests not resulting in sentencing, such as out-of-court resolutions. But the most common is “evidential difficulties”, specifically that the victim does not support taking further action.

There has been an outcry about police “overreach” and fears that officers could be “curtailing democracy” by arresting people for malicious communications offences.

The Times reported last week that Hertfordshire police sent six officers to detain a couple and put them in a cell for eight hours after their child’s primary school objected to the volume of emails they sent and “disparaging” comments on a WhatsApp group.

Maxie Allen, 50, and Rosalind Levine, 46, were questioned on suspicion of harassment, malicious communications and causing a nuisance on school property. After a five-week investigation, the police concluded that there should be no further action.

A police officer also said that elected officials could be treated as harassment suspects if they continued advocating for the couple.

Andy Prophet, chief constable of Hertfordshire, defended the arrests, saying that the force had given warnings and they were lawful, although he conceded that “with the benefit of hindsight we could have achieved the same ends in a different way”.

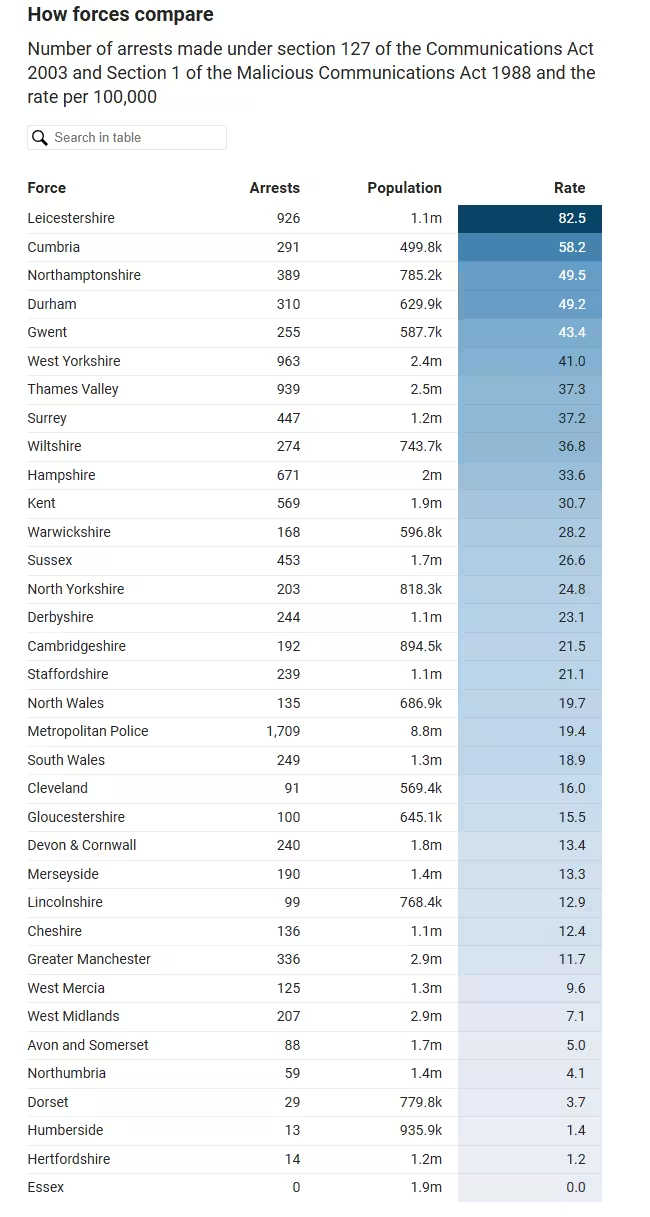

According to the data obtained by The Times, the force with the highest number of arrests in 2023 was the Metropolitan Police (1,709), the largest force in the UK, followed by West Yorkshire (963) and Thames Valley (939). However, when adjusted for population, Leicestershire police had the highest rate of arrests per 100,000 with 83. Cumbria police was second (58) and Northamptonshire police third (50).

The total arrest figures are likely to be far higher because eight forces failed to respond to freedom of information requests or provided inadequate data, including Police Scotland, the second largest force in the UK. Some forces also included arrests for “threatening” messages, though these do not fall under the specified sections.

Jake Hurfurt, head of research and investigations at Big Brother Watch, a civil liberties group, said the increase of arrests for communications offences is “seriously concerning”.

He said: “Police look to be wasting countless hours on arresting people for posting things online that, while offensive, are not illegal. Heavy-handed use of vague communications offences is a threat to everyone’s freedom to express themselves online. Police must remember that free speech is a right, and only intervene when absolutely necessary, because needless arrests for social media posts have a chilling effect that will cause the decline of our democratic culture. These statistics are seriously concerning and the home secretary should instigate an independent review into police arrests for online speech and the health of free expression in the UK.”

Toby Young, the founder and director of the Free Speech Union, said his organisation was helping half a dozen people who were being prosecuted for section 127 or section 1 offences.

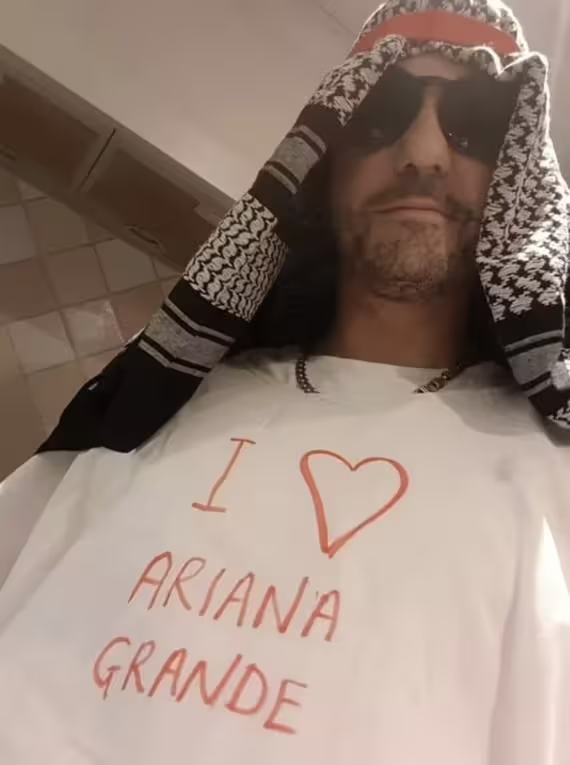

They include David Wootton, 40, who is appealing against a conviction for dressing up as the Manchester Arena bomber, Salman Abedi, for a Halloween party last year.

He had posted images on social media showing him wearing an Arabic-style headdress, and the slogan “I love Ariana Grande” on his T-shirt, and carrying a rucksack with “Boom” and “TNT” written on the front. Wootton was arrested and admitted sending an offensive message online. He faces up to two years in prison.

Young accused police forces of being “over-zealous in pursuing people for alleged speech crimes”.

“Given that only 11% of the violent and sexual offence cases in England and Wales were closed after a suspect was caught or charged in the year to June 2024, a steep decline on previous years, it seems extraordinary that the police are wasting so much time arresting people for hurty words," he added.

Sir Keir Starmer emphatically denied there is a free speech crisis in Britain when JD Vance raised this with him at the White House, but this data suggests we have a serious problem.

A suspect arrested on suspicion of malicious communications may have also been arrested on suspicion of other linked offences. So while they might not have been sentenced for that offence, they might for another offence if it was part of the same incident.

A spokeswoman for Leicestershire police said crimes under Section 127 and Section 1 include “any form of communication” such as phone calls, letters, emails and hoax calls to emergency services.

“They may also be serious domestic abuse-related crimes. Our staff must assess all of the information to determine if the threshold to record a crime has been met. Where a malicious communications offence is believed to have taken place, appropriate action will be taken. Our staff must consider whether the communication may be an expression which would be considered to be freedom of speech. While it may be unacceptable to be rude or offensive it is not unlawful — unless the communication is ‘grossly offensive’. Freedom of speech is enshrined within our society, and while communications may be rude, impolite or offensive, they may not be unlawful. Decisions are made taking this into consideration and if found not to be unlawful, will not be recorded as a crime.”

Other police forces deferred to the National Police Chiefs’ Council, which did not provide a comment.

Comments (0)