Uzbekistan reached a historic milestone at the Paris 2024 Olympics, marking its greatest achievement in Olympic history. The Uzbek team brought home an impressive total of 13 medals—eight gold, two silver, and three bronze. Among these remarkable feats, the boxing team stood out, delivering a performance for the ages by securing five of the eight gold medals.

However, there is a little-told story of an American boxer and coach who first set up a Boxing school in Uzbekistan and is generally regarded as the founding father of Uzbek boxing: Sidney Jackson, a boxer from New York. Jackson came to Tsarist Russia to see bears but couldn't leave due to the outbreak of World War I.

Sidney Jackson was born in 1886 in New York. He was raised in a poor Jewish family and lost his father at the age of six. His father, Louis Jackson, who had spent his entire life working in a chemical factory, died of tuberculosis. With the family's breadwinner gone, the children had to find work. The children worked for meager wages, and young Sid realized that a similar fate awaited him.

However, his father's friends helped him get into school, where he showed an interest in the humanities. Despite being a good student, Sid chose his profession by chance. One day, a classmate brought a sports magazine to school featuring strong boxers. It was then that Jackson decided he wanted to become one of them.

Sid was 12 years old when he and a friend joined the Bronx Ridgeon Club. Initially, he felt awkward in the ring, but after persistent training, he adapted and became more precise in his movements. Soon, the aspiring athlete began participating in amateur competitions. Meanwhile, he still needed to earn money, so Sid took a job as a courier, reassuring himself that he was exercising his legs while delivering orders. As his fights increased and the fees from them became sufficient, he no longer needed to work in a chemical factory.

By 1914, the young boxer had already reached a professional level. He was selected for the U.S. national team and traveled around the world. However, his career ended before it could truly begin. In a decisive fight in Glasgow, Sidney broke his thumb and had to leave the ring for six months. To avoid being stuck at home, the athlete decided to go to Russia, as he put it, "to see the bears roaming the streets." Jackson, along with his boxer friend Frank Jill, arrived at the Arkhangelsk port in mid-summer and was met with a lot of impressions, unfortunately not all positive.

"Everywhere we went, we were greeted by ruined houses and destroyed bridges, noisy hotels, and drunk people wandering around," Jackson recalled. "Because the sky was cloudy, we couldn't even see the stars."

-9sBf02TH.jpeg)

Dissatisfied with their experience, the visitors took the first train to St. Petersburg and then to Moscow. After settling into the "National" Hotel, they read in the newspaper that World War I had begun. Not wanting to be caught in the center of the conflict, the boxers contacted the U.S. consulate and were informed that the evacuation route to the west was blocked. As a result, they were offered temporary relocation to Tashkent. They sent a telegram home asking for money for the return ticket, but only Jill received a wire transfer. It later turned out that Sid's mother had not received his messages because she had moved from New York to California, worried about her eldest son's health after he contracted tuberculosis. Even if she had received the messages, she had no money to send to her son. Realizing that he couldn't even afford to stay in the cheapest hotel, Jackson turned to the governor-general for help finding a job. Since boxing was not practiced in Central Asia at that time, Sid was forced to work as an assistant to a tailor. He was very hardworking but regretted that his efforts would have been more beneficial in training.

Sidney lived in a narrow hut in an old neighborhood where other immigrants also resided. By interacting with them, he soon became fluent in Russian and gained a rudimentary understanding of politics. In 1918, when the Civil War broke out, Jackson volunteered to serve in the International Brigade of the Red Army. During his four years of service, Sid fought in battles across Central Asia and the Caucasus, sustaining injuries twice. After the war, he returned to Tashkent, where he worked as a sports instructor for the Universal Military Training (Vsevobuch) and then was appointed to a sports club where he began teaching boxing to children. Sidney made everything needed for the classes himself, using available materials.

-FuoKgU8u.jpeg)

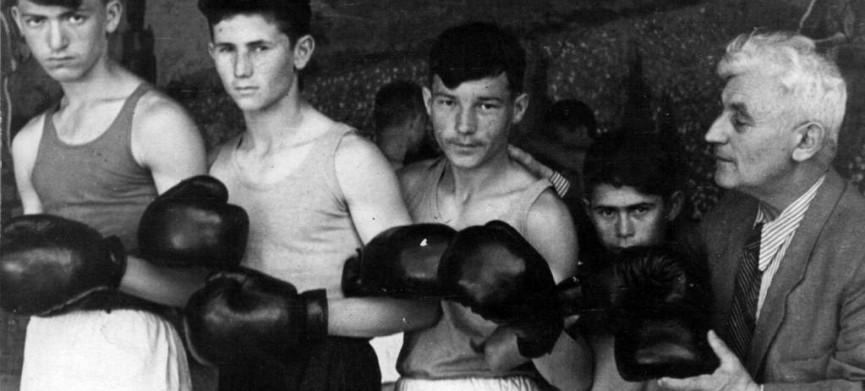

He made a boxing ring from ship ropes, patched up three pairs of worn-out gloves, and sewed a few new boxing gloves using leather from a local slaughterhouse and horsehair. The coach also made punching bags from old sacks. Thus began the history of the first boxing club in the USSR, established by an American Jew.

-GPVTazle.jpeg)

Many of his students in Tashkent went on to become famous boxers and coaches themselves among them Vladimir Agaronov, Joseph Budman, Boris Granatkin, Yori Bochman, and the Luxemburg brothers living in Israel.All of his students expressed gratitude to him. Malik Babaev, Senior Specialist of the Boxing Federation of Uzbekistan in 2022, expressed his warm thoughts on Sidney Jackson:

“There are many interesting and important pages in the history of boxing in Uzbekistan. There were moments of greatness; there were moments when our sportsmen did not do so well, but all that taken together, I can say Sidney laid an excellent foundation for our boxing to become today among the strongest in the world, and the indications of recent years prove that we are on the right path. Without a doubt, I express gratitude to the founder, the father of boxing in our country”

Along with making critical contributions to the growth of the boxing sport in Uzbekistan, Mr. Sidney Jackson also spread the American culture, which was well cited by the former US Ambassador in Uzbekistan:

“Sidney Jackson was a pioneer in U.S-Uzbekistan people-to-people ties. He didn’t know he was. It was an accident he ended up in Tashkent really by a twist of fate as we would say. Being there during the war, not being able to leave, and then finding a home, and making a home for himself in Tashkent. It was an accident but he was in a sense an ambassador of American culture in Uzbekistan”

Several government officials praise the valuable efforts of Sidney Jackson, as mentioned by Aziz Abduhakimov, Minister of Tourism and Sport of Uzbekistan:

“Sidney Jackson, the founder of uzbek boxing, arrived at a time when a new state system had just been established; of course, those were very difficult times, but his zeal to develop sport and his love for boxing, we can see the results in the way our uzbek boxers compete very successfully nowadays in many international competitions.”

His students didn't just box—Jackson, always cheerful and full of energy, also taught the youth other sports, including swimming, athletics, and football. The boys loved their coach, who believed in them more than they believed in themselves. However, in 1921, what Sid had long awaited and his pupils feared finally happened. While preparing athletes for the local Olympics, the American ambassador arrived in Tashkent with travel documents for Sid. Sidney told the ambassador that the United States had forgotten about him for seven years and that he was too late.

"A few years ago, I was ready to do anything to return home, but now everything has changed," Jackson replied. "It is a great honor to be a citizen of the United States, but it is an even greater honor to stay here and serve this country."

Despite devoting himself entirely to coaching and even obtaining Soviet citizenship in 1922, Jackson was more criticized than praised. He was accused of practicing "bourgeois sports that reject collective values," and his coaching abilities were not appreciated. At that time, the successes of the local Soviet population were highly valued, but foreigners were left out of such recognition. Jackson also endured the era of antisemitism, during which Jews were demoted or even fired from their positions. However, as Sid himself recalled, he was fortunate that "he only heard words behind his back, not the sound of bullets."

-YhrMYx6e.jpeg)

In 1929, Jackson married Berta Braginskaya, a Jewish woman from Kiev who was 20 years younger than him. The couple had two children. When mass famine struck the USSR, Sid realized he couldn't support his family with boxing. The 47-year-old coach decided to become an English teacher.

"My toughest fight was between Russian and English grammar," Jackson joked.

But Sidney won this fight too—he soon began teaching English at the Foreign Languages Institute and earned the title of professor at the age of 50.

In the classroom, Sidney was the calm Professor Jackson, enthusiastically reading Mark Twain to his students, but among the young boxers, he became "Grandpa Sid." Every morning, he would storm into the Pioneers' Palace like a whirlwind. His student, the journalist and Hero of the Soviet Union Vladimir Karpov, later recalled that Jackson could not stand laziness and had no sympathy for anyone. "We trained every morning and every evening, focusing on endurance and strength. Grandpa Sid demanded strict discipline from us and hated drinking and idleness. The training sessions were so intense that you would never forget them," Karpov said.

Sidney Jackson remained the head coach of boxing in the Uzbek SSR for many years and in 1957, after training more than ten successful athletes, he was awarded the title of Honored Coach of the USSR. He stayed in good physical shape until his last days. For example, at the age of 79, he traveled with his team to Tallinn, on the other side of the Union. Six months earlier, he had undergone surgery to remove a stomach tumor but continued living as if nothing had happened. When he visited his son, he walked effortlessly through the mountains. "He walked faster than me despite the pain, while I struggled with shortness of breath," Leo recalled. However, no matter how strong and determined Jackson was, he could not overcome cancer. On January 5, 1966, three months before his 80th birthday, "Grandpa Sid" passed away.

"Sometimes I think it's time to stop, but even thinking about it scares me. I'm not young, but I still believe that saying 'I can't' is just an excuse. How can an old man like me live with this feeling? Time can't stop me; it will take something stronger to defeat me," Jackson once said.

Comments (0)