Corruption most prevalent in education, healthcare, and banking sectors in Uzbekistan, Senate reports

Follow Daryo's official Instagram, LinkedIn, and Twitter pages to keep current on world news

Uzbekistan joins international initiative to protect children from violence

"Joining the partnership opens up new opportunities for Uzbekistan: learning from the experience of other countries, exchanging effective practices, and using global expertise. This is an important step towards protecting children in partnership with the global community," said Shakhnoza Mirziyoyeva, First Deputy Director of the National Agency for Social Protection.

Uzbekistan to abolish 30 types of documents as public services expand

Mirziyoyev invites Trump to Uzbekistan during telephone call on strategic partnership

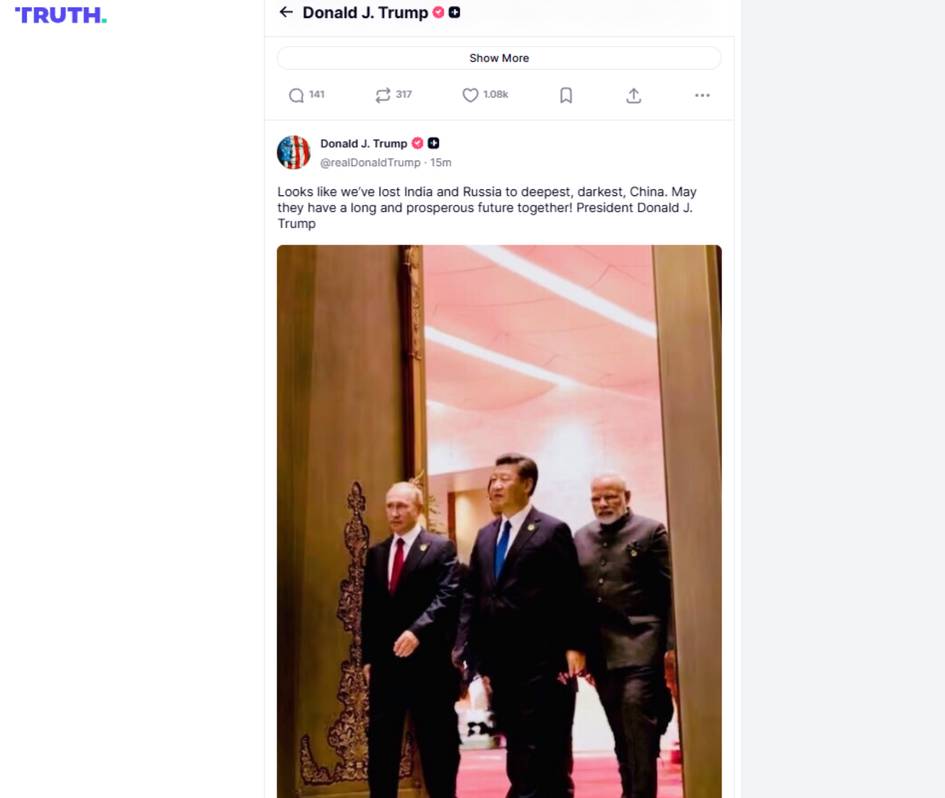

Beyond a Paper Tiger: How Russia, China, India, and Central Asia are building Eurasia’s future through the SCO

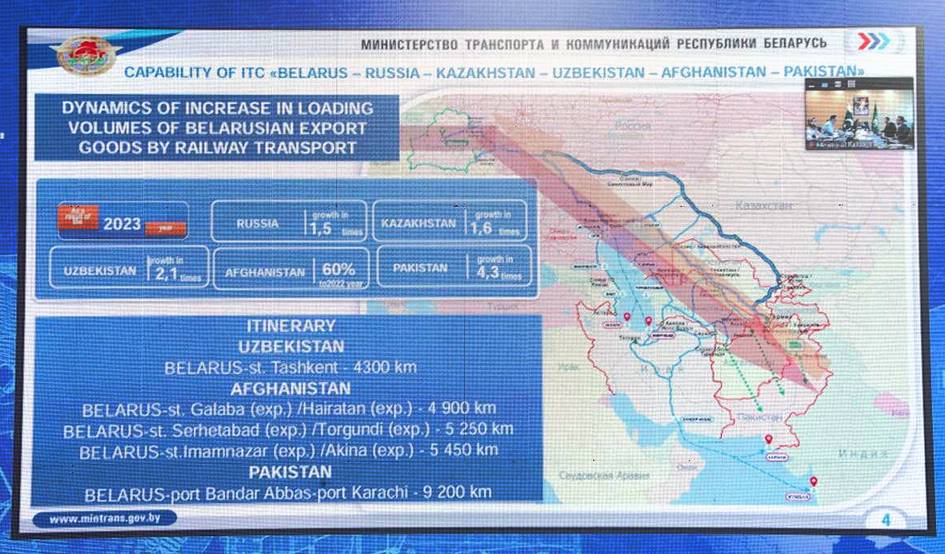

Eurasian energy and transport integration at the 2025 SCO summit

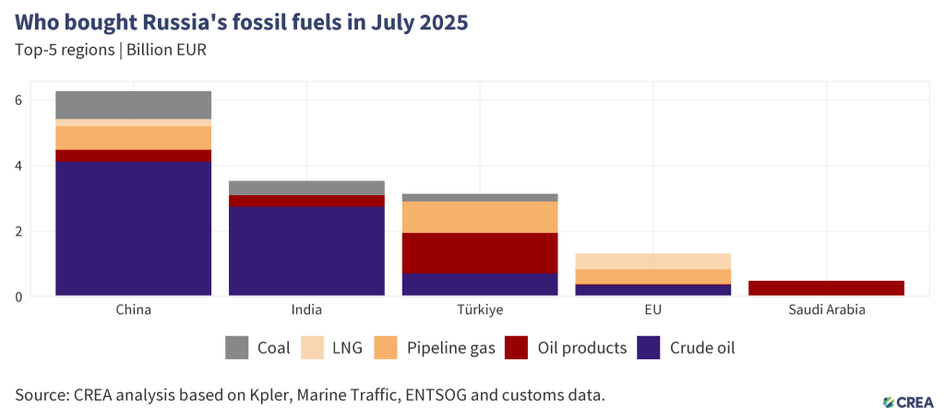

The September 2025 summit marked a turning point in Eurasia’s energy and economic policy. China and Russia signed a legally binding memorandum to build the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline, linking Western Siberian gas fields to China through Mongolia. With a planned capacity of 50bn cubic meters per year, the project will far exceed the existing Power of Siberia pipeline.

For Moscow, the pipeline secures a new major export market after losing access to European consumers. For Beijing, it provides a stable, long-term source of energy in an era of geopolitical risks and import diversification. China also announced expanded cooperation in renewable energy with Russia and other regional states, alongside his call to establish a SCO Development Bank as soon as possible to finance projects through grants and loans.

These moves reinforced the rapid growth of Russia’s oil trade with China and India, establishing the SCO’s energy partnership as a shield against Western sanctions. Pricing and purchase volumes under Power of Siberia 2 remain unresolved, yet the signing itself strengthened Moscow and Beijing’s role as leaders of Eurasian energy integration.

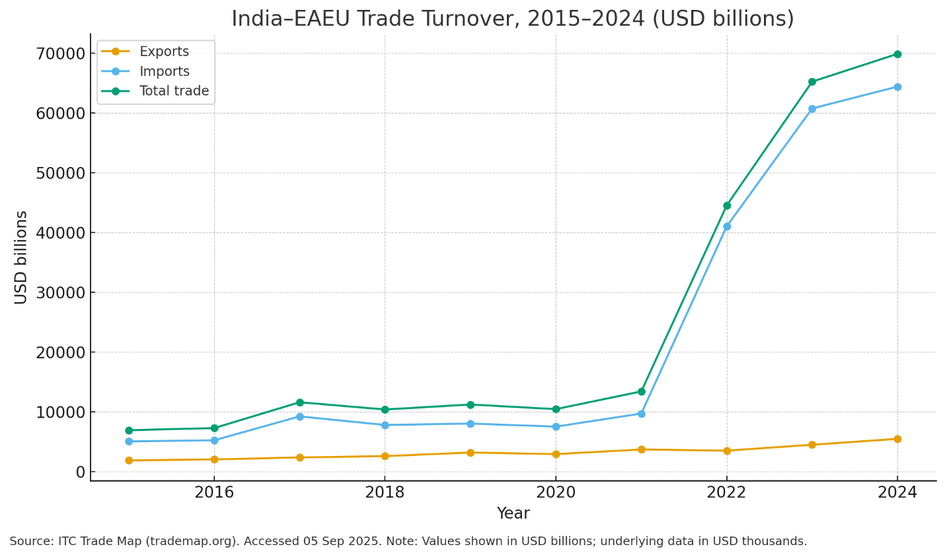

India’s economic shift

India’s strategy also reached a critical point. In August 2025, Washington imposed 50% tariffs on a wide range of Indian exports, from textiles to chemicals, in response to continued purchases of Russian oil. The tariffs sharply reduced India’s access to the U.S. market, threatening up to a 70% collapse in key export sectors.

Rejecting U.S. tariffs as unjustified, Indian leaders reaffirmed their course of strategic autonomy. Sanctions and tariffs thus acted as a catalyst for building new hubs of energy and transport in Eurasia, where China, Russia, and India are gradually shaping alternative power centers less dependent on U.S. and EU markets.

Central Asia’s dual role

Ghosting the SCO: West Skips the Parade, Sweats the Photo

Western media and analysts cast the optics, especially the image of Xi, Putin, Kim, and Pezeshkian together, as an “axis of upheaval” aimed at the U.S.-led order, and European security voices warned the display reinforced Moscow’s claim that it can endure because it has powerful friends. The collective absence signaled a refusal to legitimize what many in the West view as an explicitly anti-Western coalition.

The administration tightened pressure on New Delhi over sanctions compliance even as critics pointed to a paradox, since U.S. tariffs and other unilateral measures, singled out in the summit’s language, may be accelerating non-Western alignment. Policy circles rallied around friend-shoring and control of chokepoints in finance, supply chains, and technology, with scenarios ranging from managed transactionalism to harder bifurcation or crisis-driven polarization. The prevailing view is that the unipolar moment is ending and the United States must adapt to a more complex multipolar order where even democratic partners exercise strategic autonomy.

Conclusion

The SCO’s recent evolution shows both promise and limits. It has become a framework for Eurasian energy and transport integration, reinforced by Russia–China pipeline projects, India’s Eurasian pivot, and Central Asia’s bridging role. Yet the experience of Iran demonstrates the shortcomings, so Asia Times.

Beeline Uzbekistan started 2025 with a significant network modernization

Corruption most prevalent in education, healthcare, and banking sectors in Uzbekistan, Senate reports

Uzbekistan joins international initiative to protect children from violence

More than 500,000 new users: residents of Uzbekistan choose the Hambi superapp

Uzbekistan

Corruption most prevalent in education, healthcare, and banking sectors in Uzbekistan, Senate reports

Uzbekistan’s Senate has spotlighted education, healthcare, banking, and employment services as the sectors hit hardest by corruption, warning of rising cases in key regions and adopting new measures to tighten prevention and oversight.

Uzbekistan joins international initiative to protect children from violence

Uzbekistan to abolish 30 types of documents as public services expand

Mirziyoyev invites Trump to Uzbekistan during telephone call on strategic partnership

Beyond a Paper Tiger: How Russia, China, India, and Central Asia are building Eurasia’s future through the SCO

25 000 sum / per month

Buy subscription

World

Uzbekistan could be affected by radiation from Iran in certain weather conditions, expert says

Iran as the pressure point: How Washington’s campaign against Tehran seeks to undercut China and Russia - and why Central Asia risks the fallout

Russia to write off $300mn Tajikistan electricity debt

Central Asia–China Summit yields new agreements on trade, connectivity, and culture

Russia officially recognizes Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan

As a symbolic gesture, the Afghan flag introduced by the Taliban was raised for the first time over the Afghan Embassy in Moscow.

Daryo+

"The young man, feeling the breath of death, knelt down and kissed the shoes of the executioners" - the harrowing story of witnesses to the civil war in Tajikistan

The 1990s were a challenging and turbulent period for the countries of the former Soviet Union. The collapse of the “Red Empire” triggered severe ethnic, religious, and political conflicts in several nations. Newly independent states such as Tajikistan, Georgia, Moldova, Azerbaijan, and Armenia found themselves engulfed in civil wars and armed conflicts. “Daryo” presents the stories of individuals who witnessed and endured the atrocities of the Tajik civil war (1992–1997), a conflict that claimed thousands of lives.

From Ruble zone to global fintech leader: Kazakhstan’s financial revolution in focus

Trump’s foreign policy in Central Asia: balancing acts amid rising influence from China and Russia

The implication of Israel-Iran War for Central Asia

India’s Chabahar Port investment: navigating Eurasian trade through geopolitical tensions

Live

Latest News

Corruption most prevalent in education, healthcare, and banking sectors in Uzbekistan, Senate reports

Uzbekistan joins international initiative to protect children from violence

Uzbekistan to abolish 30 types of documents as public services expand

Mirziyoyev invites Trump to Uzbekistan during telephone call on strategic partnership

Beyond a Paper Tiger: How Russia, China, India, and Central Asia are building Eurasia’s future through the SCO

Recommendations

Lifestyle and Culture

Chinese woman offers apartment in Shanghai as reward to whoever finds her son who was lost 26 years ago

Imam Al-Bukhari and Sukarno: A cross-cultural journey supported by global philanthropy

Imam Al-Bukhari and Sukarno, a theatrical-musical production celebrating the shared cultural heritage of Indonesia and Uzbekistan, had its world premiere in Samarkand in November 2024. Featuring over 60 performers, the play brings to life the journey of Indonesia’s first president, Sukarno, to Uzbekistan in 1956. "This project represents a cultural dialogue," says Restu Imansari Kusumaningrum, the play's Artistic Director. "The arts need to be supported, not just by the government, but by the community—by private donors and philanthropists. Without them, many of these stories would remain untold." With a production cost of over $100,000, the production showcases the crucial role of private sector support in making such cultural initiatives a reality.

Sport

Uzbekistan joins Asian Cricket Council, strengthening regional ties

Uzbekistan to introduce three-stage youth sports championship with Presidential Olympics final

Uzbekistan and Azerbaijan aim to host FIFA U-20 World Cup 2027 with joint bid

Uzbekistan’s president reviews proposals to prepare for 2028 Olympic and Paralympic games

Manchester City owner sets sights on Uzbekistan’s football future

Money

Show business

Uzbek Deputy Minister's criticism sparks controversy over X-Factor show

Renowned singer Shuhrat Daryo echoed the deputy minister's sentiments, expressing his disappointment for Uzbek art and the nation as a whole after watching the show.

Burt Young, Oscar-nominated 'Rocky' star, passes away at 83

Former NFL star Michael Oher wins conservatorship battle against 'The Blind Side' inspirers, Tuohys

Irish actor Sir Michael Gambon passes away at 82, leaving profound void in entertainment

Good news:

Tags

Grow your business with us

Advertise on Daryo.uzIndividual approach and exclusive materials

Ad-free site readingSubscribe

25 000 sum per month